Elena Dopazo: We propose »

|

|

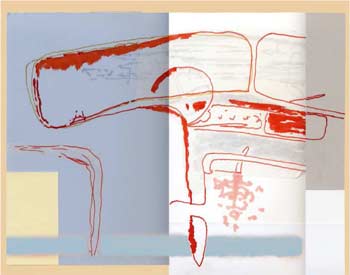

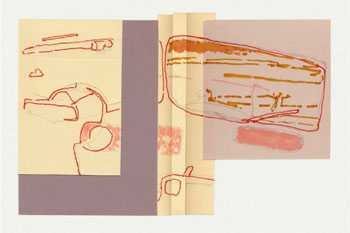

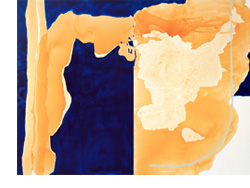

Parapla III: (…) And providence offered me a vision of an agrarian knee tucked into a tobacco coloured stocking l Digital print on paper. Single original. 108 x 150 cm |

Parapla VII. Digital print on paper. Single original. 108,97 x 150 cm |

RAFAEL SATRÚSTEGUI: IF EVOLUTION ISN'T ONLY TO ADVANCE

Elena Dopazo

Evolution can be understood in the widest of senses, even retreat can sometimes be a sensible form of evolution.

The case of Rafael Satrústegui draws attention due to the wisdom of its result.

A 47-year old from Madrid with extensive experience in exhibits, public and private collections, he seems to have approached youthful movements in his more recent work: which is fresher, more irresponsible, more experimental. He himself divides his work into “Not Snapshots” and “Photo collages”.

The former play effectively with the instant and with chance (a chance that, as it could not be otherwise, is strictly premeditated) combining two worlds: one that Rafael calls “fictitious” - that of the painting – and the real one, determined by the physical demands of the space in which the works find themselves. The result is superb, a third outlet, treated digitally, that creates a higher appreciative level. This level hasn't merely joined them, but has confused them, not knowing where the work or the artist's universe begins (if, after all, it hasn't always been the same thing).

Dominated by pastel colours, by scenes that have been violated by elements of daily life – a chair, a bicycle... - the result is delicate, elegant, but strong and satisfactory (with the bonus of them being, quite often, single, original pieces).

The second part of this renewal exercise, once certain spiritual and ironic lines have been overcome, leads him to grant a primordial importance to words in his pieces: therein divesting photography of its documentary character, that imposed reflection of likelihood, in order to attain poetry. Is he successful? Yes.

By using contemporary technological media, Satrústegui does not avoid traditional methods, he does not reject paint as this is another caprice that manages to reflect reality. Thus, what turns out to be a photograph has passed through the sieve of painting, the complex world of the object inserted into the work as art (he inserts it onto the canvas, in the photograph, as a pure visual form) and, finally, words.

Words are lodged in the titles, but far from being mere explanatory elements or shapers of their meaning, they have become yet another character in the final result: the pieces close themselves around their captions.

It is not at all easy to take on change. We usually settle for those things we know how to achieve and what we know how to admire: it is equally difficult to take on a new role in our creative work as it is difficult for a loyal spectator to recognise himself in new habits. Yet despite this, Rafael Satrústegui jumps the barrier, recognises and is recognised. For that we applaud him.

|

|

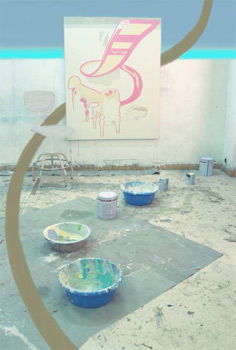

Swaying, egocentric and pink.Digital print on paper. Single copy. 70 x 100 cm |

A pause on the way. Digital print on paper. Single copy. 100 x 70 cm |

|

|

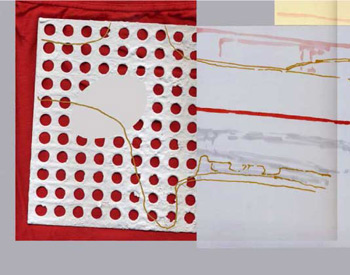

Loquacious. Digital print on paper. Single copy. 70 x 100 cm |

Parapla I: (…) Those ladies – I thought when I saw them – will not get very far (…). Digital print on paper. |

Pablo Jiménez: Catalogue for the exhibition "Barnices", Astarté Gallery, Madrid, 2001 »

PAINTING AS A WHOLE

Pablo Jiménez

Rafael Satrustegui belongs to a generation of artists which bears its most significant traits

in the return to painting in a context which would appear to necessarily conceive artistic

practice in other forms, as is the case here. Modern History of Art, and the modern world

in general, makes us feel closer to certain artistic languages at certain times, and thus

obiects, painting itself, different settings and photography reveal themselves in the

magical and favourable space of the present-day, thereby disqualifying all other forms of

artistic language.

Rafael Satrustegui belongs to a generation of artists which bears its most significant traits

in the return to painting in a context which would appear to necessarily conceive artistic

practice in other forms, as is the case here. Modern History of Art, and the modern world

in general, makes us feel closer to certain artistic languages at certain times, and thus

obiects, painting itself, different settings and photography reveal themselves in the

magical and favourable space of the present-day, thereby disqualifying all other forms of

artistic language.

Even at times when painting has relished in that special brilliance dated by the modernity of the present-day, there has been much discussion to identify to what extent figurative art is acceptable and from which point the still-life supporters should return. And without even having to abandon the field of painting, it should be remembered that not so long ago we were talking about ‘new figuration‘, which has nothing whatsoever to do with the ‘new realists‘, ‘new objectivity‘ or the "neorealists‘ or "neoromanticists". All this confusing relabelling and new labels have logically arisen from a need and not only a need.

It should not be forgotten that "modernity" and ‘fashion‘ go hand in hand, and that the oonstant demand for new things makes utter, tragic and devastating sense, forming one of the traits of the modern world. Conciliation between this imperative and the traditional idea of art, which tends towards timelessness and immortality, is one, but not the only or the most shocking one, of the contradictions of art as we understand it today.

This long drawn out introduction is not intended to iustify anything, and even less to boast of special perspicacity. The aim is simply to situate the work of an artist with a very special production. An artist who is particularly anxious to size up and shape exactly what he has to say, and yet, an artist with extraordinarily clear and limpid diction.

There is a general unspoken agreement that exhibition catalogues should commence with words of praise and explanations of the works reproduced within. As in the case of all unspoken agreements, this is fairly senseless. Art and painting demand complicity and it is down to the viewer whether he accepts them and shares feelings, sensations and emotions or whether he rejects them and goes on to something else. And this will occur however intellectual or tear-jerking the introduction may be.

And this is all the more unnecessary if the viewer has already seen the works at this exhibition. Rafael Satrustegui has always been the most refined and exquisite of artists, trying to communicate his view in the most subtle of ways, with overflowing sensitivity and good taste. Not to be forgotten is his ease of working in the language of paint, always limiting resources employed.

On this occasion he follows a formal approach which is fundamentally based on the use of varnish as colour and paint. The technique is not new in itself, for dare we say that the very Tapies himself used. The interesting point is that the varriish is not used as worthless material used once again by the artist, or as watercolour technique to permit subtle transparencies. Here, the varnish is a constructive element in the painting which plays with colour on even terms, with the white of the canvas, but which also takes form in the emphatic and impressive appearance of a figuration, without suffering complexes at all.

This exhibition is a lesson in good painting. Painting which holds,no fear in exploring all possible paths within certain ranges, which are limited as always, and which have a general tone, or dare I say, a general feeling, which gives the very why and wherefore to the painting as a whole.

Once again, Rafael Satrustegui shows himself to be sure and convincing in his

painting techniques. He reveals his fantastic gifts as an artist, capable of employing a

multitude of techniques and approaches. The huge self-portrait which should preside this

exhibition (which the artist himself calls ‘Surge of light‘) is clearly a memorable work with

regard to its references to art of the past (it brings to mind Rembrandt and his

engravings), and the full and emphatic freedom derived from the most radical of the

traditions of modernity.

Once again, Rafael Satrustegui shows himself to be sure and convincing in his

painting techniques. He reveals his fantastic gifts as an artist, capable of employing a

multitude of techniques and approaches. The huge self-portrait which should preside this

exhibition (which the artist himself calls ‘Surge of light‘) is clearly a memorable work with

regard to its references to art of the past (it brings to mind Rembrandt and his

engravings), and the full and emphatic freedom derived from the most radical of the

traditions of modernity.

The main part of the exhibition and work of Rafael Satrfistegui falls between these two references. lt is easy to find the intensity, sensitivity and power of evocation which allow us to pretend that we can share with someone sensations, feelings, fears and tenderness which we would hardly be capable of putting into words. Through his works, the world is revealed to us as beautiful, diverse and tremendously rich in its smallest variations. And art in turn is revealed as a magic world which permits us to broaden our perception of all things.

His work is serene, but full of intense details. Rafael Satrustegui restores in us a pleasure for art; art in all its fullness and wide range. As a language enclosed in itself, and as a language which is open to that magical act of recognising familiar faces and forms. This is painting as a whole; you iust have to try to see it.

Pablo Jiménez

Rafael Satrustegui belongs to a generation of artists which bears its most significant traits

in the return to painting in a context which would appear to necessarily conceive artistic

practice in other forms, as is the case here. Modern History of Art, and the modern world

in general, makes us feel closer to certain artistic languages at certain times, and thus

obiects, painting itself, different settings and photography reveal themselves in the

magical and favourable space of the present-day, thereby disqualifying all other forms of

artistic language.

Rafael Satrustegui belongs to a generation of artists which bears its most significant traits

in the return to painting in a context which would appear to necessarily conceive artistic

practice in other forms, as is the case here. Modern History of Art, and the modern world

in general, makes us feel closer to certain artistic languages at certain times, and thus

obiects, painting itself, different settings and photography reveal themselves in the

magical and favourable space of the present-day, thereby disqualifying all other forms of

artistic language.Even at times when painting has relished in that special brilliance dated by the modernity of the present-day, there has been much discussion to identify to what extent figurative art is acceptable and from which point the still-life supporters should return. And without even having to abandon the field of painting, it should be remembered that not so long ago we were talking about ‘new figuration‘, which has nothing whatsoever to do with the ‘new realists‘, ‘new objectivity‘ or the "neorealists‘ or "neoromanticists". All this confusing relabelling and new labels have logically arisen from a need and not only a need.

It should not be forgotten that "modernity" and ‘fashion‘ go hand in hand, and that the oonstant demand for new things makes utter, tragic and devastating sense, forming one of the traits of the modern world. Conciliation between this imperative and the traditional idea of art, which tends towards timelessness and immortality, is one, but not the only or the most shocking one, of the contradictions of art as we understand it today.

This long drawn out introduction is not intended to iustify anything, and even less to boast of special perspicacity. The aim is simply to situate the work of an artist with a very special production. An artist who is particularly anxious to size up and shape exactly what he has to say, and yet, an artist with extraordinarily clear and limpid diction.

There is a general unspoken agreement that exhibition catalogues should commence with words of praise and explanations of the works reproduced within. As in the case of all unspoken agreements, this is fairly senseless. Art and painting demand complicity and it is down to the viewer whether he accepts them and shares feelings, sensations and emotions or whether he rejects them and goes on to something else. And this will occur however intellectual or tear-jerking the introduction may be.

And this is all the more unnecessary if the viewer has already seen the works at this exhibition. Rafael Satrustegui has always been the most refined and exquisite of artists, trying to communicate his view in the most subtle of ways, with overflowing sensitivity and good taste. Not to be forgotten is his ease of working in the language of paint, always limiting resources employed.

On this occasion he follows a formal approach which is fundamentally based on the use of varnish as colour and paint. The technique is not new in itself, for dare we say that the very Tapies himself used. The interesting point is that the varriish is not used as worthless material used once again by the artist, or as watercolour technique to permit subtle transparencies. Here, the varnish is a constructive element in the painting which plays with colour on even terms, with the white of the canvas, but which also takes form in the emphatic and impressive appearance of a figuration, without suffering complexes at all.

This exhibition is a lesson in good painting. Painting which holds,no fear in exploring all possible paths within certain ranges, which are limited as always, and which have a general tone, or dare I say, a general feeling, which gives the very why and wherefore to the painting as a whole.

Once again, Rafael Satrustegui shows himself to be sure and convincing in his

painting techniques. He reveals his fantastic gifts as an artist, capable of employing a

multitude of techniques and approaches. The huge self-portrait which should preside this

exhibition (which the artist himself calls ‘Surge of light‘) is clearly a memorable work with

regard to its references to art of the past (it brings to mind Rembrandt and his

engravings), and the full and emphatic freedom derived from the most radical of the

traditions of modernity.

Once again, Rafael Satrustegui shows himself to be sure and convincing in his

painting techniques. He reveals his fantastic gifts as an artist, capable of employing a

multitude of techniques and approaches. The huge self-portrait which should preside this

exhibition (which the artist himself calls ‘Surge of light‘) is clearly a memorable work with

regard to its references to art of the past (it brings to mind Rembrandt and his

engravings), and the full and emphatic freedom derived from the most radical of the

traditions of modernity.The main part of the exhibition and work of Rafael Satrfistegui falls between these two references. lt is easy to find the intensity, sensitivity and power of evocation which allow us to pretend that we can share with someone sensations, feelings, fears and tenderness which we would hardly be capable of putting into words. Through his works, the world is revealed to us as beautiful, diverse and tremendously rich in its smallest variations. And art in turn is revealed as a magic world which permits us to broaden our perception of all things.

His work is serene, but full of intense details. Rafael Satrustegui restores in us a pleasure for art; art in all its fullness and wide range. As a language enclosed in itself, and as a language which is open to that magical act of recognising familiar faces and forms. This is painting as a whole; you iust have to try to see it.

Abel H. Pozuelo: Published in El Cultural 1999 »

RAFA SATRÚSTEGUI

Abel H. Pozuelo

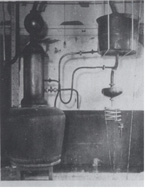

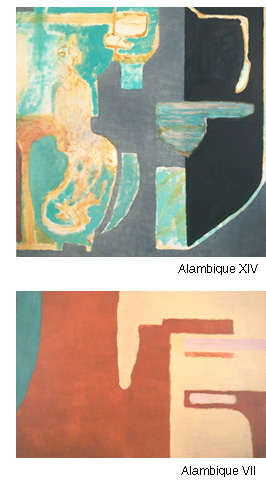

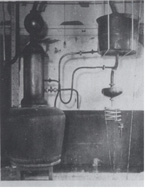

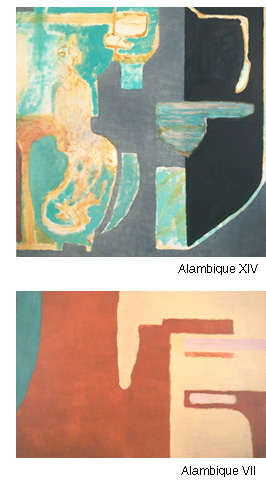

The fourteen paintings that Rafael Satrústegui (Madrid, 1960) exhibits in Madrid these days took an antique rum still as their starting point. Within its photographic image the painter saw the possibility of a flow for his paintings, as well as a shape from which to depart on a journey with no turning back. The still: an expansive figure, not constrictive, through which liquid flows and transforms itself.

With it he encountered a metaphor that shone a light on an open and unbeaten road, a painting willing to refer to itself without further ado, capable of always going forward, without exhausting itself.

With his latest pieces he demonstrates the correctness of the proposal, composing images where the reverberation of light, their vibrations, take centre stage. Subject matter that is capable of providing a hipnotic peace, the pieces in Satrústegui fugue act as stained glass windows in Gothic cathedrals used to: they are circuit diagram as well as maps; they justify their being by themselves, and indicate a road to follow.

Abel H. Pozuelo

The fourteen paintings that Rafael Satrústegui (Madrid, 1960) exhibits in Madrid these days took an antique rum still as their starting point. Within its photographic image the painter saw the possibility of a flow for his paintings, as well as a shape from which to depart on a journey with no turning back. The still: an expansive figure, not constrictive, through which liquid flows and transforms itself.

With it he encountered a metaphor that shone a light on an open and unbeaten road, a painting willing to refer to itself without further ado, capable of always going forward, without exhausting itself.

With his latest pieces he demonstrates the correctness of the proposal, composing images where the reverberation of light, their vibrations, take centre stage. Subject matter that is capable of providing a hipnotic peace, the pieces in Satrústegui fugue act as stained glass windows in Gothic cathedrals used to: they are circuit diagram as well as maps; they justify their being by themselves, and indicate a road to follow.

Juan Manuel Bonet: Catalogue for the exhibition “Alambiques”, Barcelona Gallery, 1.998 »

Juan Manuel Bonet

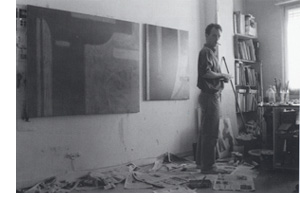

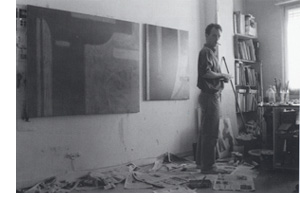

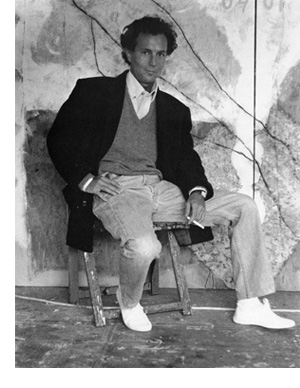

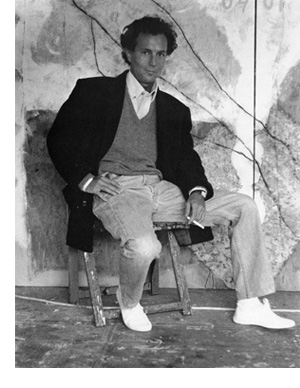

Rafael Satrústegui, in his tall and naked studio on calle Velázquez, a good address for a painter who experiences painting as something above time, a studio with lots of light, and a very ample view - “almost an Antonio López”, yes – above the rooftops of Madrid, his native city, where he studied fine arts. A few months ago he returned from San Sebastian, where his family is from, where he'd been living for a few years, and to which he has paid homage in a 1994 painting, that is called, plainly, Donosti; pure luminous mist. Rafael Satrústegui concentrated, more than ever, in an essential pictorial project. Rather irritated about the current state of the Spanish artistic medium, so politically correct, but determined, to forge on, on his own path.

Rafael Satrústegui, in his tall and naked studio on calle Velázquez, a good address for a painter who experiences painting as something above time, a studio with lots of light, and a very ample view - “almost an Antonio López”, yes – above the rooftops of Madrid, his native city, where he studied fine arts. A few months ago he returned from San Sebastian, where his family is from, where he'd been living for a few years, and to which he has paid homage in a 1994 painting, that is called, plainly, Donosti; pure luminous mist. Rafael Satrústegui concentrated, more than ever, in an essential pictorial project. Rather irritated about the current state of the Spanish artistic medium, so politically correct, but determined, to forge on, on his own path.

Ever since I have known him, Satrústegui has worked, just like some of the other better members of the generation that he belongs to, in a lyrical, abstract key, demonstrating to have assimilated both the teachings of our own fifities' generation, but also those of the great North Americans, from among whom, very significantly, he does not choose Pollock, the inventor of dripping, as a cult figure, but rather Rothko, master of the sublime.

Along with his long-standing capacity for poetry, and his constant interest in the line, in what is graphic, for some time now a firm constructive sense has been making its way in Satrústegui's painting. Within the excellent collective that Santos Amestoy dedicated to the Lyrics of the Fin de Siècle (former MEAC, Madrid, 1996), Alejandro Corujeira and he were the ones who were most inclined in this way.

If in the case of the Argentinian the most evident reference for this starting point was Torres García, prophet of sensitive geometry, for that of the madrileño those radiant and dancing canvases caught my attention due to a certain organic constructivism, which made me think, ad lib, in the abstract and at the same time marine Wladyslaw Strzeminski of the thirties, of Strzeminski, yes, that Polish geometrist whose work I then made Satrústegui discover, and which excited him, - “I believe it will help me to proceed with what I have in hand”, he told me in a letter from San Sebastian, dated the 1st of March of that year – with that enthusiasm that the pusuers of a truth have, when they discover a predecessor, a spiritual brother.

As starting point of the paintings that are going to be a part of his second individual show in Galería Barcelona, the photograph of an unusual and large object, which caught Satrústegui's attention in an advertisement that appeared in the supplements of the Sunday papers: “the first still used to make Bacardi Rum in their distillery of Santiago de Cuba”. The still, perhaps a metaphor for the creative process, and a pretext for a series of formal variations, which are articulated in drawings in a scattered way, almost Gordillesque, in a machine-like and labyrinthine way, while the canvases tend to be more compact.

As starting point of the paintings that are going to be a part of his second individual show in Galería Barcelona, the photograph of an unusual and large object, which caught Satrústegui's attention in an advertisement that appeared in the supplements of the Sunday papers: “the first still used to make Bacardi Rum in their distillery of Santiago de Cuba”. The still, perhaps a metaphor for the creative process, and a pretext for a series of formal variations, which are articulated in drawings in a scattered way, almost Gordillesque, in a machine-like and labyrinthine way, while the canvases tend to be more compact.

As is habitual in painting, otherwise, this starting point, very visible within the striking and, stating the obvious, stilled compositions called number one and two in the series, and still discernible as a shadow in number six, that starting point with a taste of the Caribbean and of music and of the night, ends up dissolving itself.

A geometry that tempt the painter and at the same time makes him a little fearful, because he is worried it might lock him, constrain him, close off paths. Daring and refined chromatic searches, to which the painter refers in common musical metaphors. A diffuse sense of landscape, and it must be said that in that sense Alambique / Still XIII is almost a hidden and pleasantly post-impressionistic garden, and that something similar happens with Alambique / Still XIV, while most of the surface of Alambique / Still XV/III is occupied by a green space, which looks somewhat like a meadow.

A very wise modulation of light. Sketcherly notations which have much to do with the refined graphics of the canvases included in Lyrics of the Fin de Siècle... I find these recent paintings that Satrústegui shows me, truly remarkable. All these things, all these “ingredients” merge in them quite naturally. Calm paintings, and at the same time, populated with enigmas. Paintings in which geometry is compatible with tremor.

I especially like Alambique / Still V, with its exaggeratedly horizontal, panoramic format (28 x 104 cm) – we find a similar one in Alambique / Still XII (22 x 139 cm) - , its ochres and its reds, its imprecise contours which radiate light, its magical atmosphere, a little unreal, and Alambique / Still XI, also in light shades, presided by a kind of large arch, and with a couple of horizontal bands that resemble clouds, as well as Rothkian bands. Even more essential, from my point of view Alambique / Still VII, one of the larger sizes (130 x 195 cm) takes the cake. In this one, everything from the composition to the colours - whitish ochres, duns, greens -, contributes to a sense of monumentality, abundance, brightness, stillness. From this definitive image, which expands the project that Satrústegui is embarked on, it is conceivable that access to even larger formats would suit these paintings. Formats, for example, of the kind that the Swiss Helmut Federle, whose studio in Vienna I visited last year, and whose works can be seen in a couple of months at the IVAM, handles.

Even more essential, from my point of view Alambique / Still VII, one of the larger sizes (130 x 195 cm) takes the cake. In this one, everything from the composition to the colours - whitish ochres, duns, greens -, contributes to a sense of monumentality, abundance, brightness, stillness. From this definitive image, which expands the project that Satrústegui is embarked on, it is conceivable that access to even larger formats would suit these paintings. Formats, for example, of the kind that the Swiss Helmut Federle, whose studio in Vienna I visited last year, and whose works can be seen in a couple of months at the IVAM, handles.

Matisse, Strzeminski, Torres García, yesterday Gioirgio Morandi's silent still lives and today those by Juan José Aquerreta, the luminous and happy, Southern landscapes by Bonnard, the melancholy sea-scapes by San Sebastian's Gonzalo Chillida, Hokusai, and in general Japanese wood carvers, Richard Diebenkorn and his dazzling Californian Ocean Parks, Ben Nicholson, Tapies, James Brown, Sean Scully, Rothko always and above everyone else, Rothko to whom one always returns, Rothko fascinating even in his preliminaries in the thirties, that taste of the Italian Novecento, and then in his transitional paintings from the Forties, disjointed, impregnated with surrealis and mythology...

These and a few other tutelary figures emerge in our rushed conversation on site – the Czech Josef Sima also makes an appearance, with his central European woodlands and his French plains, so essential and pure to be almost mystical -, these and a few other figures, as part of the imaginary museum of a contemporary painter, of a restless long-distance runner, who is often in doubt, but who pursues calm, and who for some time now knows that he belongs to the family of those who believe in paintings without adjectives, and of whom I get the impression, that what concerns and impassions him most is not the body of work behind him, but the adventure of the painting that lies ahead, the painting that has yet to be painted.

Rafael Satrústegui, in his tall and naked studio on calle Velázquez, a good address for a painter who experiences painting as something above time, a studio with lots of light, and a very ample view - “almost an Antonio López”, yes – above the rooftops of Madrid, his native city, where he studied fine arts. A few months ago he returned from San Sebastian, where his family is from, where he'd been living for a few years, and to which he has paid homage in a 1994 painting, that is called, plainly, Donosti; pure luminous mist. Rafael Satrústegui concentrated, more than ever, in an essential pictorial project. Rather irritated about the current state of the Spanish artistic medium, so politically correct, but determined, to forge on, on his own path.

Rafael Satrústegui, in his tall and naked studio on calle Velázquez, a good address for a painter who experiences painting as something above time, a studio with lots of light, and a very ample view - “almost an Antonio López”, yes – above the rooftops of Madrid, his native city, where he studied fine arts. A few months ago he returned from San Sebastian, where his family is from, where he'd been living for a few years, and to which he has paid homage in a 1994 painting, that is called, plainly, Donosti; pure luminous mist. Rafael Satrústegui concentrated, more than ever, in an essential pictorial project. Rather irritated about the current state of the Spanish artistic medium, so politically correct, but determined, to forge on, on his own path.Ever since I have known him, Satrústegui has worked, just like some of the other better members of the generation that he belongs to, in a lyrical, abstract key, demonstrating to have assimilated both the teachings of our own fifities' generation, but also those of the great North Americans, from among whom, very significantly, he does not choose Pollock, the inventor of dripping, as a cult figure, but rather Rothko, master of the sublime.

Along with his long-standing capacity for poetry, and his constant interest in the line, in what is graphic, for some time now a firm constructive sense has been making its way in Satrústegui's painting. Within the excellent collective that Santos Amestoy dedicated to the Lyrics of the Fin de Siècle (former MEAC, Madrid, 1996), Alejandro Corujeira and he were the ones who were most inclined in this way.

If in the case of the Argentinian the most evident reference for this starting point was Torres García, prophet of sensitive geometry, for that of the madrileño those radiant and dancing canvases caught my attention due to a certain organic constructivism, which made me think, ad lib, in the abstract and at the same time marine Wladyslaw Strzeminski of the thirties, of Strzeminski, yes, that Polish geometrist whose work I then made Satrústegui discover, and which excited him, - “I believe it will help me to proceed with what I have in hand”, he told me in a letter from San Sebastian, dated the 1st of March of that year – with that enthusiasm that the pusuers of a truth have, when they discover a predecessor, a spiritual brother.

As starting point of the paintings that are going to be a part of his second individual show in Galería Barcelona, the photograph of an unusual and large object, which caught Satrústegui's attention in an advertisement that appeared in the supplements of the Sunday papers: “the first still used to make Bacardi Rum in their distillery of Santiago de Cuba”. The still, perhaps a metaphor for the creative process, and a pretext for a series of formal variations, which are articulated in drawings in a scattered way, almost Gordillesque, in a machine-like and labyrinthine way, while the canvases tend to be more compact.

As starting point of the paintings that are going to be a part of his second individual show in Galería Barcelona, the photograph of an unusual and large object, which caught Satrústegui's attention in an advertisement that appeared in the supplements of the Sunday papers: “the first still used to make Bacardi Rum in their distillery of Santiago de Cuba”. The still, perhaps a metaphor for the creative process, and a pretext for a series of formal variations, which are articulated in drawings in a scattered way, almost Gordillesque, in a machine-like and labyrinthine way, while the canvases tend to be more compact. As is habitual in painting, otherwise, this starting point, very visible within the striking and, stating the obvious, stilled compositions called number one and two in the series, and still discernible as a shadow in number six, that starting point with a taste of the Caribbean and of music and of the night, ends up dissolving itself.

A geometry that tempt the painter and at the same time makes him a little fearful, because he is worried it might lock him, constrain him, close off paths. Daring and refined chromatic searches, to which the painter refers in common musical metaphors. A diffuse sense of landscape, and it must be said that in that sense Alambique / Still XIII is almost a hidden and pleasantly post-impressionistic garden, and that something similar happens with Alambique / Still XIV, while most of the surface of Alambique / Still XV/III is occupied by a green space, which looks somewhat like a meadow.

A very wise modulation of light. Sketcherly notations which have much to do with the refined graphics of the canvases included in Lyrics of the Fin de Siècle... I find these recent paintings that Satrústegui shows me, truly remarkable. All these things, all these “ingredients” merge in them quite naturally. Calm paintings, and at the same time, populated with enigmas. Paintings in which geometry is compatible with tremor.

I especially like Alambique / Still V, with its exaggeratedly horizontal, panoramic format (28 x 104 cm) – we find a similar one in Alambique / Still XII (22 x 139 cm) - , its ochres and its reds, its imprecise contours which radiate light, its magical atmosphere, a little unreal, and Alambique / Still XI, also in light shades, presided by a kind of large arch, and with a couple of horizontal bands that resemble clouds, as well as Rothkian bands.

Even more essential, from my point of view Alambique / Still VII, one of the larger sizes (130 x 195 cm) takes the cake. In this one, everything from the composition to the colours - whitish ochres, duns, greens -, contributes to a sense of monumentality, abundance, brightness, stillness. From this definitive image, which expands the project that Satrústegui is embarked on, it is conceivable that access to even larger formats would suit these paintings. Formats, for example, of the kind that the Swiss Helmut Federle, whose studio in Vienna I visited last year, and whose works can be seen in a couple of months at the IVAM, handles.

Even more essential, from my point of view Alambique / Still VII, one of the larger sizes (130 x 195 cm) takes the cake. In this one, everything from the composition to the colours - whitish ochres, duns, greens -, contributes to a sense of monumentality, abundance, brightness, stillness. From this definitive image, which expands the project that Satrústegui is embarked on, it is conceivable that access to even larger formats would suit these paintings. Formats, for example, of the kind that the Swiss Helmut Federle, whose studio in Vienna I visited last year, and whose works can be seen in a couple of months at the IVAM, handles.Matisse, Strzeminski, Torres García, yesterday Gioirgio Morandi's silent still lives and today those by Juan José Aquerreta, the luminous and happy, Southern landscapes by Bonnard, the melancholy sea-scapes by San Sebastian's Gonzalo Chillida, Hokusai, and in general Japanese wood carvers, Richard Diebenkorn and his dazzling Californian Ocean Parks, Ben Nicholson, Tapies, James Brown, Sean Scully, Rothko always and above everyone else, Rothko to whom one always returns, Rothko fascinating even in his preliminaries in the thirties, that taste of the Italian Novecento, and then in his transitional paintings from the Forties, disjointed, impregnated with surrealis and mythology...

These and a few other tutelary figures emerge in our rushed conversation on site – the Czech Josef Sima also makes an appearance, with his central European woodlands and his French plains, so essential and pure to be almost mystical -, these and a few other figures, as part of the imaginary museum of a contemporary painter, of a restless long-distance runner, who is often in doubt, but who pursues calm, and who for some time now knows that he belongs to the family of those who believe in paintings without adjectives, and of whom I get the impression, that what concerns and impassions him most is not the body of work behind him, but the adventure of the painting that lies ahead, the painting that has yet to be painted.

Miguel Fernández Cid: Artists in Madrid »

Miguel Fernández Cid:

With San Sebastian ancestry and links, Rafael Satrústegui (Madrid 1960) had a short stint at the “Contemporary Art Workshops” at the Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid, limiting his assistance to the course that was taught by Darío Villalba, one of the more fruitful in view of its results. Of the connection that was established between them, there is irrefutable proof: when at the end of the season the Juana Mordó gallery organises a collective of young artists, Satrústegui is invited to participate in an election after which it is easy to see the praise by Villalba; when the latter repeats the workshop in Arte-Leku (San Sebastian), almost three years later, he has him as a student again.

With San Sebastian ancestry and links, Rafael Satrústegui (Madrid 1960) had a short stint at the “Contemporary Art Workshops” at the Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid, limiting his assistance to the course that was taught by Darío Villalba, one of the more fruitful in view of its results. Of the connection that was established between them, there is irrefutable proof: when at the end of the season the Juana Mordó gallery organises a collective of young artists, Satrústegui is invited to participate in an election after which it is easy to see the praise by Villalba; when the latter repeats the workshop in Arte-Leku (San Sebastian), almost three years later, he has him as a student again.

A reproduction of a painting of his occupies the main space on one of the walls of his studio, converted in something like a disparate breviary of affinities. The connection could have been established in the attitude, the way to deal with the work, the lack of complacency that darío preaches and Rafael spaces out in long, descriptive titles, which are more ironic than poetic.

When, in the Summer of '85 he exhibits in Juana Mordó and in the final summary of the “Workshops” (in one of the editions with the more remarkable results), he has had a solo exhibit in the Alga gallery, in San Sebastian (1981), and taken part in the notorious '83 'Arteder' in Bilbao. After a few years of silence, he reappears in various collectives, with more continuous incursions from September 1988 onwards, with solo exhibits at the Dieciséis gallery in San Sebastian, the Viennese Ariadne, and Emilio Navarro in Madrid. A trio that is difficult to outline, at least at first stake, and which demonstrates the different perspectives from which Satrústegui's work stretches.

In the exhibited paintings, he showed a passionate, voracious manner, which led him to provoke distorsions, dynamic games with appearances, always maintaining a well-defined structural interest. The breadth of resources, of which the aforementioned wall is proof: paintings by Lascaux and Egyptian or Assyrian reliefs, together with Piero and Leonardo; Motherwell and Twombly together with Lindstrom and Zush. Statement and construction, excess and restraint. In '90 he returns solo to the Dieciséis Gallery, in '81 to Emilio Navarro, with whom he has attended several European contemporary art fairs. He has been selected in “Proposal 89” and “Proposal 91” of the Círculo de Bellas Artes, as well as in the 1989 Valparaiso biennial.

With San Sebastian ancestry and links, Rafael Satrústegui (Madrid 1960) had a short stint at the “Contemporary Art Workshops” at the Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid, limiting his assistance to the course that was taught by Darío Villalba, one of the more fruitful in view of its results. Of the connection that was established between them, there is irrefutable proof: when at the end of the season the Juana Mordó gallery organises a collective of young artists, Satrústegui is invited to participate in an election after which it is easy to see the praise by Villalba; when the latter repeats the workshop in Arte-Leku (San Sebastian), almost three years later, he has him as a student again.

With San Sebastian ancestry and links, Rafael Satrústegui (Madrid 1960) had a short stint at the “Contemporary Art Workshops” at the Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid, limiting his assistance to the course that was taught by Darío Villalba, one of the more fruitful in view of its results. Of the connection that was established between them, there is irrefutable proof: when at the end of the season the Juana Mordó gallery organises a collective of young artists, Satrústegui is invited to participate in an election after which it is easy to see the praise by Villalba; when the latter repeats the workshop in Arte-Leku (San Sebastian), almost three years later, he has him as a student again.A reproduction of a painting of his occupies the main space on one of the walls of his studio, converted in something like a disparate breviary of affinities. The connection could have been established in the attitude, the way to deal with the work, the lack of complacency that darío preaches and Rafael spaces out in long, descriptive titles, which are more ironic than poetic.

When, in the Summer of '85 he exhibits in Juana Mordó and in the final summary of the “Workshops” (in one of the editions with the more remarkable results), he has had a solo exhibit in the Alga gallery, in San Sebastian (1981), and taken part in the notorious '83 'Arteder' in Bilbao. After a few years of silence, he reappears in various collectives, with more continuous incursions from September 1988 onwards, with solo exhibits at the Dieciséis gallery in San Sebastian, the Viennese Ariadne, and Emilio Navarro in Madrid. A trio that is difficult to outline, at least at first stake, and which demonstrates the different perspectives from which Satrústegui's work stretches.

In the exhibited paintings, he showed a passionate, voracious manner, which led him to provoke distorsions, dynamic games with appearances, always maintaining a well-defined structural interest. The breadth of resources, of which the aforementioned wall is proof: paintings by Lascaux and Egyptian or Assyrian reliefs, together with Piero and Leonardo; Motherwell and Twombly together with Lindstrom and Zush. Statement and construction, excess and restraint. In '90 he returns solo to the Dieciséis Gallery, in '81 to Emilio Navarro, with whom he has attended several European contemporary art fairs. He has been selected in “Proposal 89” and “Proposal 91” of the Círculo de Bellas Artes, as well as in the 1989 Valparaiso biennial.

Pablo Jiménez: Catalogue “Abducted Reflections”, Emilio Navarro Gallery, 1991 »

MEMORY AND CONTAINMENT: ALL THE YESTERDAYS

Pablo Jiménez

With his exhibition of last year, Rafael Satrústegui managed, despite his surprising omission from numerous exhibitions that promoted young art in our country, to formulate different accents within a common current among artists of his generation, and demonstrate there was still room to venture possibilities capable of returning to painting all its sobriety and all its fascination. From a language that still owed a fair bit to Abstract Expressionism and in which some aspects of transvanguardism appeared – harder to trace -, but already with elements which continue to remain in his latest work – such as the muted colour, rich in greys – Rafael Satrústegui established a balance between the strong, expressive gesture and a general sedate and, somehow, content appearance. Something which, acording to his own fears, brought him closer to the threshold of a certain sense of elegance, very typical, on the other hand, of our best painting from the so-called generation of the Fifties.

With his exhibition of last year, Rafael Satrústegui managed, despite his surprising omission from numerous exhibitions that promoted young art in our country, to formulate different accents within a common current among artists of his generation, and demonstrate there was still room to venture possibilities capable of returning to painting all its sobriety and all its fascination. From a language that still owed a fair bit to Abstract Expressionism and in which some aspects of transvanguardism appeared – harder to trace -, but already with elements which continue to remain in his latest work – such as the muted colour, rich in greys – Rafael Satrústegui established a balance between the strong, expressive gesture and a general sedate and, somehow, content appearance. Something which, acording to his own fears, brought him closer to the threshold of a certain sense of elegance, very typical, on the other hand, of our best painting from the so-called generation of the Fifties.

Now, in this his second solo exhibition in Madrid, one of Rafael Satrústegui's intentions was precisely to distance himself from all manner of sensationalism, of all trace os aestheticism; to renounce a rethoric that seemed to be more the fruit of a certain insecurity, than substantially required by the demands of his own language. In part as a result of this the pieces of this exhibition have renounced to many qualities of painting itself, reducing the number of elements at play, to become centered – by means of the collage of printed textiles and the successful combination of varnishes with whites and blacks – intensifying the value of the grey tones, now more formed in semitones and nuances.

The problems that Satrústegui considers are to be found within the tradition of painting itself: representation and the value of the sign as a dual element in the plane. A sign that manages to keep, at the same time, its semantic and strictly pictorial values in a synthesis that lies beyond traditional dichotomies between abstraction and reality. Therefore, his painting can maintain, and even renew, in this new sense, clearly expressive resources – such as that of composition – which seemed almost forgotten and almost completely relegated to the alphabets postulated prior to the Sixties.

The apparent link between all these pieces is an oval shape with almost organic connotations, which is repeated within an ensemble that is rich with scattered iconography, but united by a system of open compositions which, in turn, postulate the possible infinitude of a series accidentally interrupted by the boundaries of the painting and the “necessity” of that exact moment in which the limits are determined.

All this in a counterpoint of different languages that definitely relegate references to an observed reality, in order to focus on the signs of that reality; I mean, in painting as another independent reality itself.

But precisely for that reason one can not expect that the substrate of painted and serialised fabrics have to refer back to the evocation of a particular type of environment. This is something that the paintings themselves are responsible to prevent, by focusing on much more painterly concerns, which care more about the game of supports and stresses that different forms impose on each other, than the references and interferences that are maintained with the outside world. Something that could already be glimpsed in his earlier exhibition and which postulates a type of painting sufficient in itself, as a distinct and autonomous reality.

We spoke before of composition as a resource recovered and renewed in these paintings. Paintings in which is apparent a certain very well assimilated tendency of the 80's that, among other simplifications, tends to a picture that, without leaving an obvious calligraphic expressivity, has something of an archetype, an ability to condense certain more or less fuzzy meanings , that which we used to call "sign". But that is precisely why most of the paintings with these characteristics voluntarily abandons all similarity with previous searches into the syntax of the painting itself, while Rafael Satrústegui incorporates them in a same classic sense, reconciling the two languages which, as will be evident after this exhibition, need not argue with one another.

From among these resources, the most striking is that of the composition that points at decomposition, to a tension that supports the general discourse y that is more in line with the exploration of the limits of the paining than with the imposition of a type of reality especially arresting in itself, or what is the same, serves to support the sensations and in tensities more than it does a narrative will.

Surely that is why however more disparate and more varied the signs used, the whole becomes more suggestive, even when this leads him to resort to images of a configuration that, in principle, seem somehow break the context. But the result is outright. By forcing the elements in play, the result gains an intensity by uniting the system of signs with the tension of the rest of the resources. Thus, we find ourselves before one of the most coherent, personal and forthright proposals in a long time, that we can recall in young art. Rafael Satrústegui demonstrates he is in a very lucid and productive moment, with a body of works that points towards an even braver continuation.

Pablo Jiménez

With his exhibition of last year, Rafael Satrústegui managed, despite his surprising omission from numerous exhibitions that promoted young art in our country, to formulate different accents within a common current among artists of his generation, and demonstrate there was still room to venture possibilities capable of returning to painting all its sobriety and all its fascination. From a language that still owed a fair bit to Abstract Expressionism and in which some aspects of transvanguardism appeared – harder to trace -, but already with elements which continue to remain in his latest work – such as the muted colour, rich in greys – Rafael Satrústegui established a balance between the strong, expressive gesture and a general sedate and, somehow, content appearance. Something which, acording to his own fears, brought him closer to the threshold of a certain sense of elegance, very typical, on the other hand, of our best painting from the so-called generation of the Fifties.

With his exhibition of last year, Rafael Satrústegui managed, despite his surprising omission from numerous exhibitions that promoted young art in our country, to formulate different accents within a common current among artists of his generation, and demonstrate there was still room to venture possibilities capable of returning to painting all its sobriety and all its fascination. From a language that still owed a fair bit to Abstract Expressionism and in which some aspects of transvanguardism appeared – harder to trace -, but already with elements which continue to remain in his latest work – such as the muted colour, rich in greys – Rafael Satrústegui established a balance between the strong, expressive gesture and a general sedate and, somehow, content appearance. Something which, acording to his own fears, brought him closer to the threshold of a certain sense of elegance, very typical, on the other hand, of our best painting from the so-called generation of the Fifties.Now, in this his second solo exhibition in Madrid, one of Rafael Satrústegui's intentions was precisely to distance himself from all manner of sensationalism, of all trace os aestheticism; to renounce a rethoric that seemed to be more the fruit of a certain insecurity, than substantially required by the demands of his own language. In part as a result of this the pieces of this exhibition have renounced to many qualities of painting itself, reducing the number of elements at play, to become centered – by means of the collage of printed textiles and the successful combination of varnishes with whites and blacks – intensifying the value of the grey tones, now more formed in semitones and nuances.

The problems that Satrústegui considers are to be found within the tradition of painting itself: representation and the value of the sign as a dual element in the plane. A sign that manages to keep, at the same time, its semantic and strictly pictorial values in a synthesis that lies beyond traditional dichotomies between abstraction and reality. Therefore, his painting can maintain, and even renew, in this new sense, clearly expressive resources – such as that of composition – which seemed almost forgotten and almost completely relegated to the alphabets postulated prior to the Sixties.

The apparent link between all these pieces is an oval shape with almost organic connotations, which is repeated within an ensemble that is rich with scattered iconography, but united by a system of open compositions which, in turn, postulate the possible infinitude of a series accidentally interrupted by the boundaries of the painting and the “necessity” of that exact moment in which the limits are determined.

All this in a counterpoint of different languages that definitely relegate references to an observed reality, in order to focus on the signs of that reality; I mean, in painting as another independent reality itself.

But precisely for that reason one can not expect that the substrate of painted and serialised fabrics have to refer back to the evocation of a particular type of environment. This is something that the paintings themselves are responsible to prevent, by focusing on much more painterly concerns, which care more about the game of supports and stresses that different forms impose on each other, than the references and interferences that are maintained with the outside world. Something that could already be glimpsed in his earlier exhibition and which postulates a type of painting sufficient in itself, as a distinct and autonomous reality.

We spoke before of composition as a resource recovered and renewed in these paintings. Paintings in which is apparent a certain very well assimilated tendency of the 80's that, among other simplifications, tends to a picture that, without leaving an obvious calligraphic expressivity, has something of an archetype, an ability to condense certain more or less fuzzy meanings , that which we used to call "sign". But that is precisely why most of the paintings with these characteristics voluntarily abandons all similarity with previous searches into the syntax of the painting itself, while Rafael Satrústegui incorporates them in a same classic sense, reconciling the two languages which, as will be evident after this exhibition, need not argue with one another.

From among these resources, the most striking is that of the composition that points at decomposition, to a tension that supports the general discourse y that is more in line with the exploration of the limits of the paining than with the imposition of a type of reality especially arresting in itself, or what is the same, serves to support the sensations and in tensities more than it does a narrative will.

Surely that is why however more disparate and more varied the signs used, the whole becomes more suggestive, even when this leads him to resort to images of a configuration that, in principle, seem somehow break the context. But the result is outright. By forcing the elements in play, the result gains an intensity by uniting the system of signs with the tension of the rest of the resources. Thus, we find ourselves before one of the most coherent, personal and forthright proposals in a long time, that we can recall in young art. Rafael Satrústegui demonstrates he is in a very lucid and productive moment, with a body of works that points towards an even braver continuation.